Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your academic background?

Hey there! My name is Natalia Caliani. I am originally from a little town called Coronda, in the middle of the province of Santa Fe (Argentina), famous for its strawberries.

Coming from a family of growers, I studied agricultural sciences at the National University of the Littoral. When I got to my third year, I decided that I wanted to work for the wine industry, thus, I did my honours thesis at INTA Mendoza. After falling in love with it, I moved to France and did a specialisation in water and land management, where my thesis investigated how aerial and satellite images could help establish a soil salinisation chronicle.

Back in Argentina, I spent 13 months working for a multinational enterprise (Snap-On) as a pruning specialist. In this role I provided commercial and technical support for growers in general, especially vignerons.

In 2017 I was awarded a scholarship to come to Australia and study for a Masters in Agricultural Science at the University of Western Australia. I undertook the research for my thesis on the Cabernet Sauvignon microbiome in the beautiful Margaret River region. The microbiome accounts for all the archaea, bacteria, fungi and yeasts cohabiting in the vineyard from the soil up to the grapes.

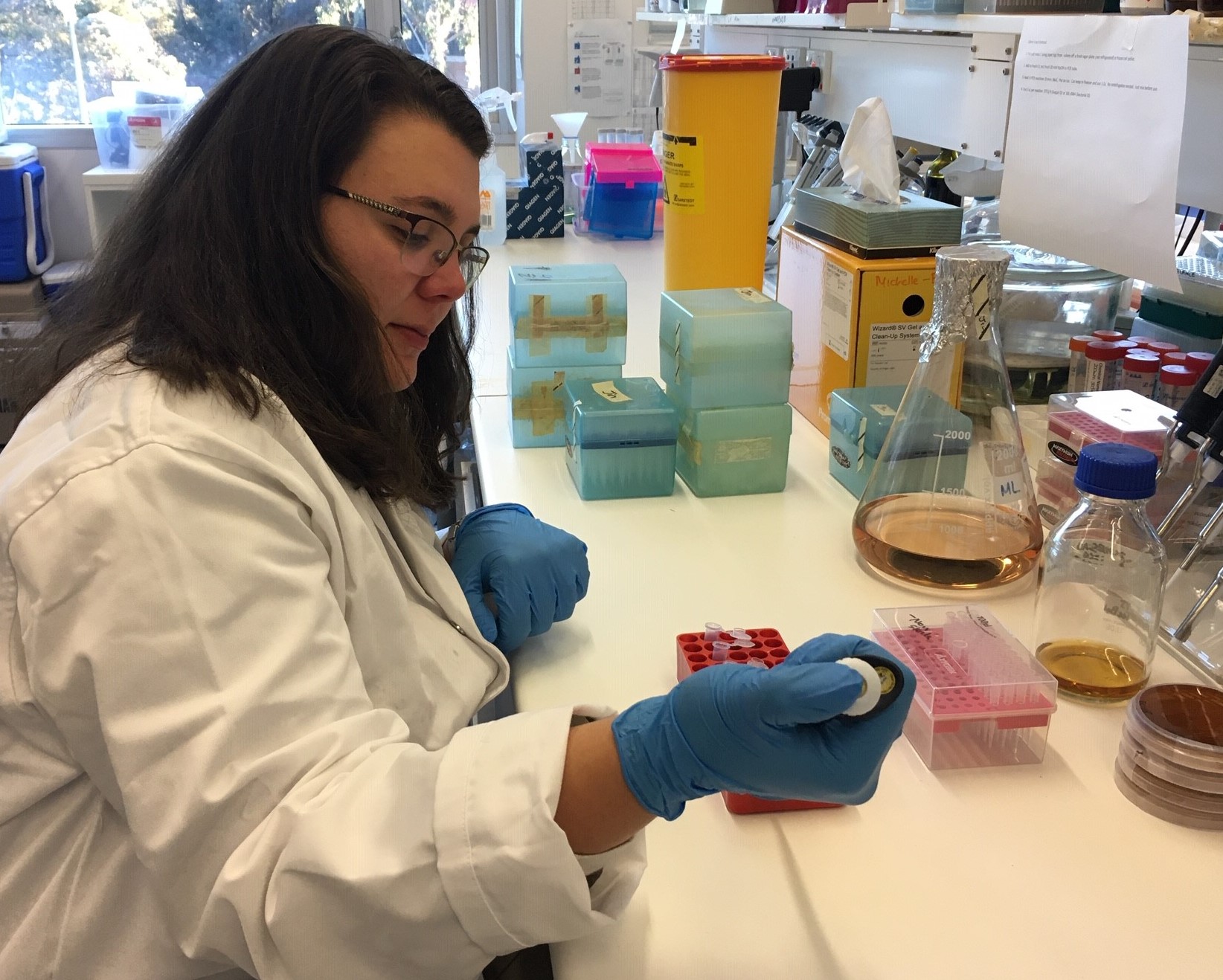

After finishing my Masters, I applied for the ARC Training Centre for Innovative Wine Production scholarship as I was interested in working with yeast, especially novel species that could have potential applications in the wine industry. And well, here I am!

Could you introduce us to your project and what it involves?

The growing desire for more interesting and innovative wine has led us to investigate yeast populations found on grape surfaces. The majority of yeast found so far are non-Saccharomyces species. These are different to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the most commonly used yeast species that winemakers worldwide use to inoculate grape juice to make wine.

These novel species are able to turn sugars into alcohol to some extent and they may also improve aromas and global perception of wine. However, there are still many things we do not know about these species and this project aims to investigate how they might be used to benefit the wine industry.

We’d like to understand how sensitive they are to wine making stresses such as ethanol and sulfur dioxide (SO2) because that will tell us how likely they are to survive during alcoholic fermentation. This information will also determine how best to exploit the potential of these new species during fermentation.

What can you see yourself doing in the future?

I see myself becoming a winemaker and running a winery, however, I’d also like to go back to the industry as a consultant. I enjoyed my previous role helping vignerons and winemakers to find solutions to problems and it would be nice to go back to that again, along with travelling and enjoying good food and wine.