Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your academic background?

I was born in Oamaru, but since most people don’t know where that is let’s just say I’m from Christchurch in New Zealand, which is where I went to University. I completed a BSc and MSc at the University of Canterbury, majoring in Microbiology. My MSc was focused on finding new ways to quickly identify Campylobacter sp., a bacteria that can cause gastroenteritis. Following that I changed to more food friendly bacteria, specifically lactic acid bacteria (LAB). I worked for a few years for Fonterra, which is a dairy research institute where I was researching dairy microorganisms and enzymes where I got to eat lots of cheese.

After a 3-year break in the UK, I moved to Adelaide and undertook a PhD in the Wine Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology Group at The University of Adelaide. Prior to moving to Adelaide I had never thought about working in the wine industry. However, after moving here I was lucky enough to get an introduction to the beautiful Waite campus and I have never left. Besides, wine and cheese go well together!

After a 3-year break in the UK, I moved to Adelaide and undertook a PhD in the Wine Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology Group at The University of Adelaide. Prior to moving to Adelaide I had never thought about working in the wine industry. However, after moving here I was lucky enough to get an introduction to the beautiful Waite campus and I have never left. Besides, wine and cheese go well together!

During my PhD I was again studying LAB, but this time I was specifically looking at their esterase enzymes and how they might be used in winemaking. Esterase enzymes are a type of enzyme that can either produce or break down esters and change the fruity aroma of wine. In red winemaking (and sometimes in whites) LAB carry out an important secondary fermentation, called malolactic fermentation (MLF). During MLF they can alter the sensory properties of the wine and the pH increases slightly. LAB contain the genes for a number of esterase enzymes and my project looked at how these might effect ester (fruity aromas) levels in wine.

After finishing my PhD, I started working on a Wine Australia project to investigate ways of improving LAB for use in winemaking. Unfortunately LAB are not always able to complete the malolactic fermentation due to the harsh conditions found in wine (like high ethanol and low pH). The aim of my project was to improve their ability to handle the harsh conditions in wine via a process called directed evolution. Directed evolution involves growing the LAB in harsh conditions and gradually increasing the stress e.g. ethanol concentration over time. This process works quite well for wine bacteria and we obtained new strains that need to be tested further in large scale-winemaking. Now I am working as a postdoctoral researcher in the ARC Training Centre for Innovative Wine Production.

Could you introduce us to your project and what it involves?

I am currently working on two microbiology projects in the ARC Training Centre for Innovative Wine Production.

The first project is called “Defining and exploiting the indigenous microflora of grapes” and involves sampling several different grape varieties grown in the same vineyard to identify what yeast are on each variety. The reason we are interested in this is the yeast present on the grapes, are the yeast that will be present during fermentation of the grape juice. If the winemaker is carrying out un-inoculated fermentation they will also be responsible for carrying out the alcoholic fermentation. The overall aim is to see whether there are differences in the yeast species that are on different grape varieties. If there are differences, I also want to understand if there is any reason for those differences. For example, is it just because of the grape variety or is it because of the colour of the grape, or because some skins are thicker?

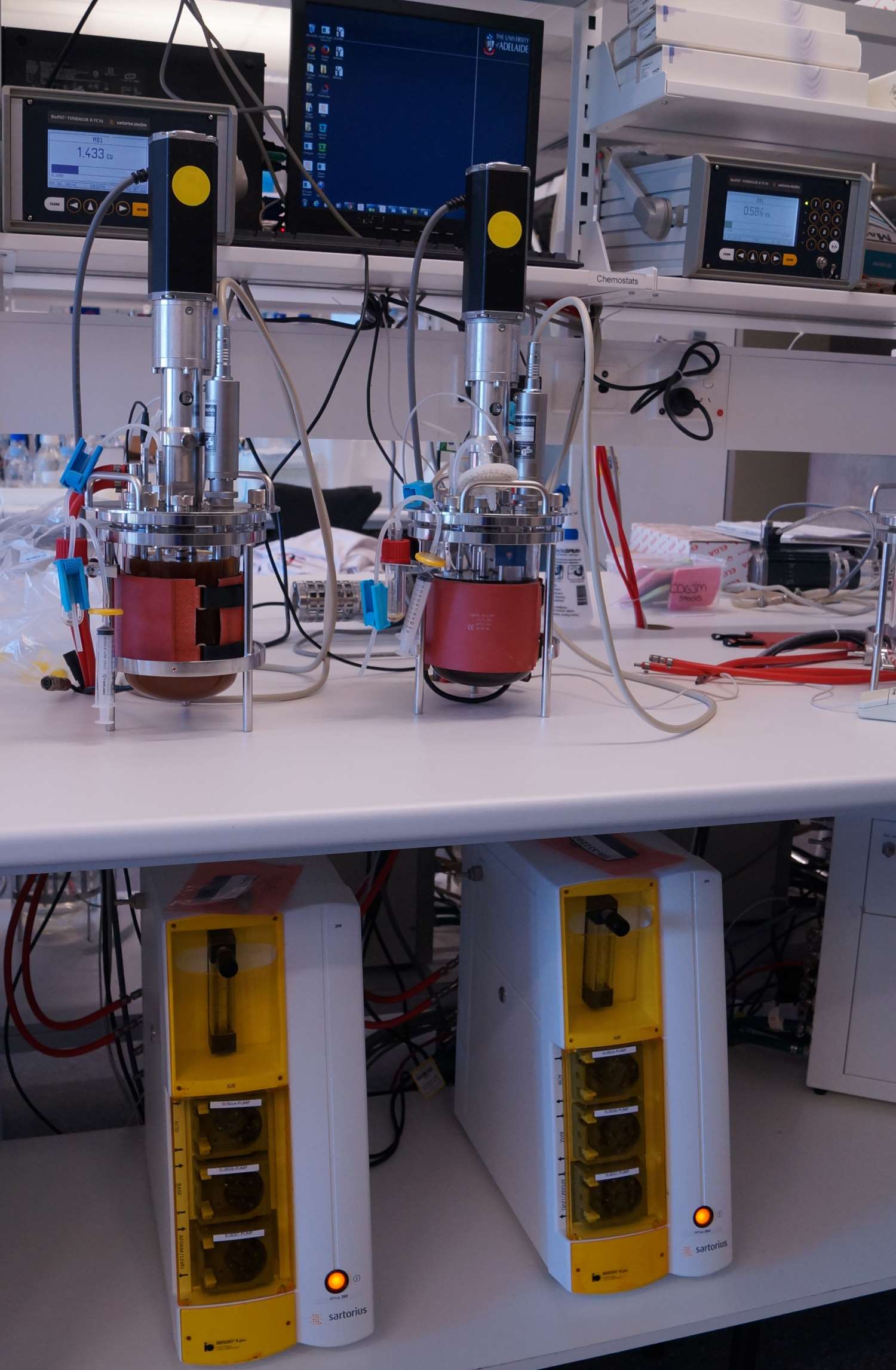

Bioreactors used for directed evolution studies. Photo: Krista Sumby

We are taking a two-pronged approach to identify the yeast found on the grape berries. The first approach is to wash the grapes to isolate and identify the yeast species; the second approach is to take whole grape berries and extract the DNA (i.e. from all of the yeast present) and then do diversity profiling. Diversity profiling is like a fingerprint and tells us the yeast species on each grape variety.

We will compare the yeast over multiple vintages to make sure that it is not a seasonal-vintage variation. In other words, we will try to see if there is a pattern. In addition to looking at the diversity of yeast on grape berries, we will see whether any of the isolated yeast can give novel attributes to wine and could be useful as pure cultures for winemakers.

The second project “Shaking up the microbiology of winemaking” aims to improve the ethanol tolerance of 1) yeast strains isolated from the first project and 2) a commercial non-Saccharomyces yeast. The commercial non-Saccharomyces strain is traditionally not very tolerant in high ethanol, but it can add more complexity to the flavour of the wine. So, we are taking a strain that we know adds good attributes to wine and we want to make it last further into fermentation, so it will be more resistant to ethanol. We are going to do that using directed evolution in a similar way to how we improved LAB strains in past work. During this process we will grow the yeast over a long period of time and gradually increase the ethanol stress.

These projects have several potential outcomes.

- We will gain more information about the yeast species on grapes and what might cause changes

- For example if you are doing an uninoculated fermentation you’ll have more information about what is likely to be in the fermentation because what is on the grape, is what is fermenting grape sugars

- To isolate yeast with novel properties that can be used to tailor certain varieties to get more reliable results every time

- To use a non-Saccharomyces strain to do the fermentation without adding Saccharomyces

What can you see yourself doing in the future?

If you had asked me 10 years ago I would have never said I would be working in the field of wine research, but here I am! In the future I would like to continue doing research. I really enjoy being involved in the wine industry and it would be great if I could continue to do research and engage with industry so that we can help deliver useful solutions.